Some of Europe’s shared characteristics can justly be called ‘brilliant’. Why must one be forced to choose, once and for all, between the detail and the whole? Neither need exclude the other: both are real.

The brilliantly clever books of Elie Faure or Count Hermann Alexander Keyserling are not in this respect completely misleading: but let us simply say that they peer too closely at the individual tiles in a mosaic which, seen from a greater distance, reveals clear overall patterns.

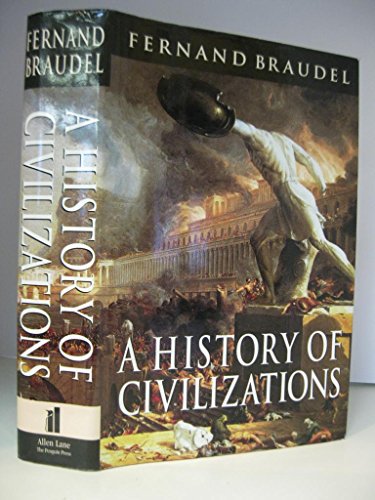

Every State has always tended to form its οwn cultural world and the study of ‘national character’ has enjoyed analysing these various limited civilizations. Nor are these national instances of unity a contradiction of Europe’s οwn. And they are not used as arguments to deny the national unity of each of the countries concerned. But they exist just as much between Brittany and Alsace, between the North and the South of France, between Piedmont and the Italian mezzogiorno between Bavaria and Prussia between Scotland and England between Flemings and Walloons in Belgium or among Catalonia, Castille and Andalusia. Such differences are abundant, vigorous and necessary. At any moment, however, it is easy to go beyond this apparent ‘harmony’ and find the national diversity that underlies it. The preceding chapters have described a number of things shared by the whole of Europe: its religion, its rationalist philosophy, its development of science and technology, its taste for revolution and social justice, its imperial adventures. Rο reply that he is both right and wrong is simply to affirm that Europe simultaneously enjoys both unity and diversity -which οn reflection seems to be the obvious truth. From Fernand Braudel, A History of Civilizations, translated by Richard Mayne, Penguin BooksĪn historian of humanism, Franco Simone, has warned us to be wary of the supposed unity of Europe: a romantic illusion, he says.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)